The More Play Changes . . .

Children have forgotten how to play.

This crisis is laid out in great detail in the pages of books and articles like Last Child in the Woods, Balanced and Barefoot, and The Overprotected Kid. The authors of these books are concerned that children today don’t play outside and are becoming disconnected from the natural world by spending their days staring screens of all sizes from monster TVs to iPhones and tablets.

And they’re not alone. As a teacher, this is a complaint I often hear from parents. It mostly comes up at the start of a new school year when I lay out to the parents how I use technology and play in my classroom. The concern usually comes in the form of “Don’t kids get too much tech already? Why can’t they play outside like we used to?”

These parents have a point. Children’s play today is very different than it was in the 1970s, 80s or any past decade. When it comes to play, however, change is not a bug, it’s a feature.

Children’s play is always changing, constantly morphing into something unrecognizable by older generations. How children play in the 21st century is merely the latest stage in the ongoing evolution of play.

Evolving Play: New Tech Means New Play

Children’s play is changing. It always has and it always will. Children’s play in 2016 (soon to be 2017) is very different than it was in the 1970s and 80s. Ubiquitous screens in the hands of children might be new, but the ever evolving nature of play is not.

To see where children’s play is going in the future, it’s useful to look to the past and see from where it came.

Perhaps the best known name in children’s psychology, Jean Piaget noted that changes in children’s play have more to do with interacting with their environment than any heredity connection to the past. He cites the example of the invention of the automobile as ushering in new forms of child’s play that involved pretending to change gears and drive what was then a brand new technology.

Even as far as the 12th century, children used the materials at hand to create games that reflected the world around them. Nicholas Orme’s look at medieval play found that in 1152, the five-year-old future earl of Pembroke used the stalks of plants to play ‘knights’, which involved hitting the stalks together to knock off the head of the plant.

With nearly a millennium worth of data on children’s imaginative play, it’s safe to say that how a child plays is not always handed down through generations but is borne from the materials at hand and the cultural zeitgeist of the time.

The Power of Play Without Purpose

In her 2015 book, Angela Hanscom highlights the view many adults have that children must be engaged and entertained at all times as being an underlying reason for children’s reluctance to venture outside for non-purposive exploration and play.

This, she argues, is not just the fault of technology and media but also a result of parents who equate their child being outside exclusively with participation in organized sports.

Whether it’s baseball or soccer, for many kids their only exposure to ‘nature’ is playing in adult-organized sporting league on fields created and maintained exclusively for that specific sport. Without the engagement of competition or a tangible end-goal reward, from participation ribbons to championship trophies children have little interest to venture outside.

If absence of extrinsic motivations decreases the desire for modern children play outside, then perhaps the absence of another element, the adults, just might get them back out there.

Adults? We Don’t Need No Adults!

In their pioneering research Iona Opie and Peter Opie conducted a survey of children’s games across the United Kingdom in the 1960s identified that kids from Aberdeen to Bristol knew how to organize their games without the guiding hands and all-seeing gaze of adults.

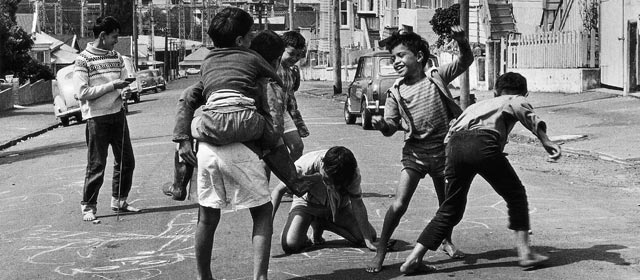

The catalogue of child-organized games is lengthy, often with intricate rules that varied from town to town up and down the country. Children had systems for choosing games, assigning roles and resolving disputes without the need for an adult to referee. In fact, often the only times adults appeared on the scene was to chastise children for playing on the grass, making too much noise or blocking the street with their “shuttlecock or tipcat”.

Nearly fifty years later, children are still fighting a turf war with adults, as demonstrated by recent stories about cities across Canada outlawing the Canadian childhood tradition of street hockey.

It seems that while children’s play has evolved over the years, the adult’s role remains constant: to police behaviour and generally get in the way. As an adult, who happens to also be a teacher, I plan on changing that.

What about you?

(Parts of this post first appeared in an academic paper for Ryerson’s Early Childhood Studies Graduate program.)

Leave a Reply